Introduction

As a follow up to Joshua and the Genocide of Canaan, I have been speaking with Christians and hearing exactly how they justify ethnic cleansing. Justifications for ethnic cleansing, you say? Yes – it is what it is. This alone should raise red flags. It should be a warning sign that something is not quite right within their moral paradigm. Nonetheless, let’s have a look.

Before beginning, it should be noted that what is described in the book of Joshua is classical genocide. This was not unheard of in ancient warfare. I mention this not to excuse it, but to get two points out of the way.

One: There are Christians who flat out deny it was genocide. They are wrong. Two: There are Christians who say genocide was acceptable in the ancient world. This is semi-correct, but misses the point. It is 2013. Not only is genocide not acceptable, but glorifying genocidal traditions is not acceptable either.

What is Genocide?

According to the UN Resolution 260 (III), the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, “genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

The conquest of Canaan fits every criteria for this definition. That it was genocide is indisputable, save for apologists inventing new definitions of the word. In the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) introduction and commentary for the book of Joshua (pg. 464) Carol Meyers wrote:

“The book’s idea of total acquisition of the land involves carrying out the command to annihilate all the inhabitants of the land (see, e.g., 6.21); carrying out this herem, or “proscription,” would have been a project of genocidal proportions.”

Nonetheless, some Christians will deny it was “real” genocide. This is akin to denying a rape is “real” rape. This level of denial borders on Orwellian Newspeak. There will be no convincing people who redefine their own terms because they dislike facing the emotional import. This post is not for them.

Interestingly, it seems most will not deny it was genocide. You can see this from the examples below. Most of the apologists cited overlap in their justifications; most make the same arguments. Naturally I have not addressed identical arguments made by different individuals. I have linked to all of their blogs, so you are free to read the nuances of their justifications in depth.

Christian Justifications of Joshua’s Genocide

Joshua should not be read in a literal context.

This is the contention of Christians such as Matt & Madeline Flannagan, who wrote, “If these passages are taken in a strict literal fashion and read in isolation from the proceeding narrative they record the divinely authorised commission of genocide.” Indeed, if the story is true (literal) then God commanded genocide. To justify this, the Flannagans cite Nicholas Wolterstorff for a non-literal interpretation: “’They left no survivors,’ etc are not intended to be read literally but function as hyperboles.” How does he arrive at the conclusion it is hyperbole, rather than literal? A reference to a contradiction in the book of Judges: “Here [in the book of Judges] it is explicitly stated that Canaanites are living in the land which had been allotted to various Israeli tribes, the land that Joshua is said to have conquered and “left no survivors.’” This is the argument in a nutshell.

Carol Meyers, who wrote the introduction and commentary for the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) version of Joshua, noted a similar point, cited in part above (pg. 464):

“The reputation of Joshua – the leader and the book – usually is based on the belief that the land was entirely conquered by Israelites in the post-Mosaic period. There are two problems with this view of the narrative, however. First, the book’s idea of total acquisition of the land involves carrying out the command to annihilate all the inhabitants of the land (see, e.g., 6.21); carrying out this herem, or “proscription,” would have been a project of genocidal proportions. Second, the intense archaeological investigation of virtually all of the places mentioned in Joshua that can be identified with current sites reveals no pattern of destruction that can be correlated, in either chronology or location, with the period of early Israel. The moral horror of the first problem may, in fact, be diminished by the historical data provided by the second. That is, the military and destructive aspects of the so-called conquest are probably not entirely historical, but rather are literary-theological constructions to portray the overarching idea of Israelite acquisition of all the land promised to the ancestors.”

Objections to a non-literal reading.

To first address what Meyers wrote: this is the mainstream historical and archaeological position. The Jewish Publication Society is not an apologetic outfit, but largely one of secular scholarship. The genocide of Canaan almost certainly did not happen. As Meyers stated, the whole thing is likely a “literary-theological construction.” This is a polite way of saying it’s fiction. While it is a relief that the genocide was not real, this does not bode well for the Bible in a religious context. Rather, it is yet another example of Biblical inaccuracy. This is fine if you understand the Bible as a unique piece of literature. It is damning if you believe that the Bible is the inerrant word of God.

In respect to the Flannagans (and incidentally Wolterstorff), a non-literal interpretation of Joshua is disingenuous. If events presented as literal are in fact hyperbolic this means the Bible is not relating history. Rather, it becomes a literary invention (as Meyers stated). If we take this position, what stops us at only interpreting the genocide as hyperbole? What if, additionally, we decide that God’s commandments, His discourses with Joshua, are not literal as well? This, too, is hyperbole. And why stop there? Perhaps God, the very idea of a divine being, is also hyperbole. This is the trap that applying non-literal interpretations to physical events falls into. It is natural to interpret a parable – something explicitly stated as a story – as non-literal. Nobody is saying that Jesus’s Parable of the Sower is intended to be literal. However, Joshua is intended to be a depiction of real events. As soon as one begins to interpret events that are presented as real as hyperbole, metaphor, or allegory it undermines Biblical exegesis in such a way that the Bible will say anything you want it to say.

An additional problem is the Flannagans/Wolterstorff using the account in Judges of the continued existence of Canaanites to justify a hyperbolic interpretation. The continued existence of Canaanites does not mean a genocide did not occur. In fact, it had already been stated (Dt. 20:10-14) that not all Canaanites would be ethnically cleansed. Rather, only those within a specific geographical boundary were to be exterminated completely. This method of interpretation becomes further problematic because it assumes that the way to reconcile the contradiction between Joshua and Judges is to interpret one as hyperbole. This is arbitrary and demonstrates a faith-based bias for Biblical inerrancy. Why not simply admit that there is a contradiction instead? Because it is already assumed, a priori, that the Bible is perfect and inerrant.

The Flannagans stated that, in essence, while there was not a complete ethnic cleansing the real goal was simply to “drive them out.” This is a position mirrored by William Lane Craig at Reasonable Faith. I fail to see how this improves the situation significantly. The Armenian Genocide involved “driving out” a people as well. As did the Rwandan Genocide. This does not make it any less morally reprehensible. It does not make it less of a genocide. At this point we are simply comparing really evil to extremely evil.

“The Jews usually didn’t fight offensive wars – only defensive.”

This is a statement made by James Rochford at Evidence Unseen. In this he quotes Paul Copan: “All sanctioned Yahweh battles beyond the time of Joshua were defensive ones, including Joshua’s battle to defend Gibeon (Josh. 10-11). Of course, while certain offensive battles took place during the time of the Judges and under David and beyond, these are not commended as ideal or exemplary.”

Objections to the genocide of Canaan being defensive in nature.

I question if Rochford has read Joshua, or even the Copan quote that he cited: both explicitly state the conquest of Canaan was offensive in nature. It may be that the battles beyond the time of Joshua were defensive (also untrue, but for a later discussion). This assertion has little to do with the conquest of Canaan. Aside from the defense of Gibeonites, who were enslaved by Joshua instead of exterminated (Jo 9:23-24), all of the conflicts in Canaan had been instigated by Israel.

The conquest of Canaan was something that had been planned long before Moses, Joshua or any of the Canaanites participants had even been born. This was ordained by God; the plan was given to Abraham and Moses (Gn 17:8; Ex 6:4). It is impossible to claim one is defending oneself from a threat that does not yet exist. In fact, the battle plan that God gave to Moses and Joshua involved invading the land, taking slaves and subjugating the people of Canaan (Dt. 20:10-14). Even the initial battles before Joshua entered Canaan proper were offensive. The native rulers went out of their way to warn Israel not to enter their borders – the borders of Edom (Nm 20:18-20), Arad (Nm 21:1-3), Bashan (Nm 21:33) and Gilead (Nm 32:39-42). Israel invaded nonetheless. Israel is described in the Bible as a foreign invading force (Gn 6:8; Ex 6:4). The Bible states that Israel was sent to invade and to dispossess (Dt 12:29) the native people of their land. It was Israel that drew first blood at Jericho and Ai. The natives of Jericho and Ai had hidden within their own city walls for safety (Jo 6; Jo 8). It was only after invading the sovereign borders of these six different kingdoms – then enslaving the Gibeonites (Jo 9:23-24) – that the remaining nations of Canaan came out to attack Israel. If anybody was fighting a defensive war it was the city-states of Canaan.

If you are still not convinced, consider the fact that Joshua went out of his way to hunt down those who fled from battle (Jo 11:10-11). Also, consider the fact that Joshua’s war of ethnic cleansing targeted not just soldiers, but the men, women, children and even animals (Jo 10:30; 10:33; 10:35; 10:39; 11:11; 11:12-14; 11:20). This was, however, only confined to central Canaan within specific geographical boundaries. God permitted the taking of slaves from more remote Canaanite cities (Dt 20:10-14).

The last sentence is very important, because a related Christian justification states this, to paraphrase: “If the Canaanites were not ethnically cleansed – even the children – they would grow up to be a threat to Israel.” The Bible indicates otherwise. God required Joshua to selectively exterminate some cities and enslave others (Dt 20:10-14). Israel was not concerned with a future threat. Joshua was just fine with keeping the entire Gibeonite population, as well as these external cities, alive and well. God allowed Joshua to take Canaanite men and women as slaves, allowing them to live and, as the argument asserts, become a threat.

The children go to heaven so it is fine to kill them.

This is the position of William Lane Craig at Reasonable Faith:

“Moreover, if we believe, as I do, that God’s grace is extended to those who die in infancy or as small children, the death of these children was actually their salvation. We are so wedded to an earthly, naturalistic perspective that we forget that those who die are happy to quit this earth for heaven’s incomparable joy. Therefore, God does these children no wrong in taking their lives.”

Objections to the assertion it is good to kill small children.

If God exists and If it is your God and If your belief that dead pagan babies go to eternal paradise is true then, I must concede, the very best thing that could have happened to those children was for Joshua to kill them. Now, let’s take this to its logical conclusion. If death is truly a small child’s salvation then to maximize salvation one would want a Joshua to kill all small children today. The best thing for those Canaanite children is identical to the best thing for all children. They are “happy to quit the earth for heaven’s incomparable joy.” In fact, if this reasoning holds true, it should be a global policy. Abortion or infanticide to ensure salvation. Ensure none even risk hell. (You should probably thank abortion doctors for doing the Lord’s work, too). Yet, I don’t see any Christians taking this ethical vehicle for a spin.

Then again, If God does not exist, or If God exists but it is not your God, or If your belief is wrong then we have another problem. Maybe they were massacred for nothing. Perhaps they went to a Canaanite hell, instead of to Canaanite heaven, without a chance. The presumption, the big If, relies upon a religious fantasy to justify an act of genocide. At this point I will point out this is the exact same type of moral reasoning that terrorists employ within their own religious paradigms. And I’m not playing the terrorist card for shock value. I mention it because William Lane Craig said it:

“The problem with Islam, then, is not that it has got the wrong moral theory; it’s that it has got the wrong God.”

You see, the moral theory behind religious violence is fine to Craig. The only issue is to make sure that you don’t have the “wrong God.”

Well, Mr. Craig, I think you have the wrong God. I believe in 10,000 Dog Demons; the Holy Spirit told me so. And since I’ve never carried out a genocide, unlike the people you idolize in the Bible, I’d say I have a higher ethical high ground to determine correct moral theory than yourself.

But the Canaanites were “bad” people.

This one comes from Robert Bowman at 4Truth.net. This position can be summed up in the famous line from Samuel L. Jackson as Carl Lee Hailey in A Time To Kill: “Yes they deserved to die and I hope they burn in hell!”

“Critics of the Old Testament’s claim that God ordered the killing of whole tribes in Canaan typically neglect the reason expressly stated in the Old Testament: those tribes were depraved beyond redemption (Gen. 15:16; Lev. 18:21-30; 20:2-5; Deut. 12:29-31; etc.). According to the Old Testament, the Canaanites and other tribes in the land widely practiced child sacrifice, incest, bestiality, and other behaviors that almost everyone in history, including today, rightly regard as unspeakably, grossly immoral.”

But what about the children? Bowman has an answer for that, too:

“First, after generations of the sort of moral degeneracy that characterized these peoples, it may be that even the smallest children were beyond civilizing...Second, the STDs and other infectious diseases that must have pervaded those cities may well have been carried by the smallest children, and if so, they may have posed a grave danger to the physical health of the Israelites.”

Read that part again, don’t miss it.

Basically the Canaanite kids had Canaan-AIDS.

Objections to rationalizing the deaths of bad people.

To begin with, it is a Biblically incorrect claim. Bowman has presented a half-truth: the Bible does describe the Canaanites as evil. However, it is not the reason for the conquest of Canaan. It does not even take an important place in the story of the conquest of Canaan.

The Bible states that the real reason – the entire premise behind Israel owning the land – are covenants that God made with Abraham and Moses (Gn 17:8; Ex 6:4). Further, it states that it is on the account of Israel that the lands are being given over to Israel (Jo 23:9). Not on account of the Canaanites; not on account of their child sacrifice, bestiality, or incest. Not even because the kids had Canaan-AIDS. It was on the account of Israel and the covenant God made with Abraham. In fact, in the entire book of Joshua the sins of the Canaanites are not mentioned. Not even once. However, the promise to Abraham is mentioned over two dozen times (1:15; 2:9; 2:14-15; 5:6; 6:16-17; 8:1; 8:7; 8:18; 10:25; 11:15; 11:23; 13:1; 13:6; 14:10; 17:4; 18:3; 19:50; 20:1; 21:2; 21:41-43; 22:4; 23:5; 23:15). It is extremely clear that the primary motivation for ethnically cleansing the Canaanites was not to bring retribution upon them for their sins, but to deliver the Promised Land.

Moreover, the “moral degeneracy” of the Canaanites may be exaggerated to aid Christian justifications for the genocide. Paul Copan – whom one of the Christians cited previously for a non-literal interpretation – rejected the premise the conquest of Canaan was due to their supreme evil. Copan wrote: “Contrary to what some Bible believers claim, the Canaanites were not the absolute worst specimens of humanity that ever existed — or the worst that existed in the ancient Near East.” The supposed evil of Canaan is a justification after the fact that rests more easily upon our moral sensibilities.

For the sake of argument let’s assume the worst – the Canaanites were wicked, evil little Hitlers. They committed incest, child sacrifice and had sex with animals. You know what is even more evil than that? The genocide of multiple ethnic groups. You know who did that? Joshua. Genocide is part of what Bowman called “behaviors that almost everyone in history, including today, rightly regard as unspeakably, grossly immoral.” Yes, by committing genocide in Canaan Joshua was acting at least – if not more – immoral than the Canaanites he was killing.

And inventing a story about evil Canaanite babies with Canaanite STDs? This is just an example of how far some Christians will to go justify immorality in the Bible. Well, maybe they had Canaan-AIDS? Yes, maybe. Therefore, probably. Therefore, certainly. Genocide justified. If the Bible does not say it and history does not record it, just invent it.

God can commit genocide, because it’s God. God does what He wants!

Most of the arguments above, including this one, tend to be shared by apologists. They mix and match. None are unique to any specific apologist. And most of the apologists quoted thus far made this argument (“God does what He wants”). In summary, God is the source of morality. If God pleases, God could order a genocide and it would be good. Not because the act of genocide is good but just because God says so. God could send everybody directly to Hell and this would be pure goodness. This is a concept closely related to theodicy, not to be confused with idiocy, but from theos and dike; God’s Justice. The term was coined in the 18th century by Gottfried Leibniz, but the concept was covered in the classical apologetics of St. Augustine and St. Irenaeus. Both the Augustinian theodicy and Irenaean theodicy sidestep the question of evil completely. For St. Augustine evil did not exist; evil was simply a lack of goodness. For Irenaeus, evil was good. Evil was necessary for free will and human development.

Neither of these theodicies justify the genocide of Canaan. Joshua received a divine order from God. It was not an act of human free will (per Irenaeus), but a command from God. Augustine denied the existence of evil. We cannot refute Augustine’s denial of evil. Evil, as a physical thing, can not be measured nor falsified. We can refute Augustine’s assertion of good, however. This segues into Euthyphro’s Dilemma. Augustine denies the existence of evil, but not good. (This is convenient, given that good can be denied just as evil can.) Nonetheless, we must ask what is the source and nature of good.

Euthyphro’s Dilemma is from Plato’s Euthyphro, a dialogue between Socrates and Euthyphro. While stated differently in the dialogue, applied in a monotheistic context it works like this:

Is something good because God commands it, or does God command things because they are good?

There are two propositions, or horns. The argument in the context of Joshua – that genocide is good because God said so – is reliant upon the first. Things are not good in and of themselves, but good is defined by God. This is a problematic assumption. It asserts far too much with far too little support: God exists and God is good. We can just as easily assert an evil God. Ironically, Christians will often claim that without God morality is arbitrary. Yet, the first horn of Euthyphro’s Dilemma is ethical subjectivism. Morality is derived from the sole and subjective whim of a deity. Good is arbitrary, not fixed. What is good may change as the subjective whims of God change. Genocide may be bad, then good, then bad again. There is no objective rule.

Even worse – this makes it impossible to distinguish good from evil. Acts that appear universally evil to us (such as genocide) may in reality be good (as God subjectively defines it). Anything that God does is automatically good. The final implication is that if we can’t distinguish good from evil we can’t know if God is truly omnibenevolent (all good) rather than truly omnimalevolent (all evil).

Think hard on that last sentence – with this position you logically cannot assert that God is good or evil, as there is no criteria for which to distinguish between the two.

Final thoughts and an evidence-based moral basis to reject the genocide of Canaan.

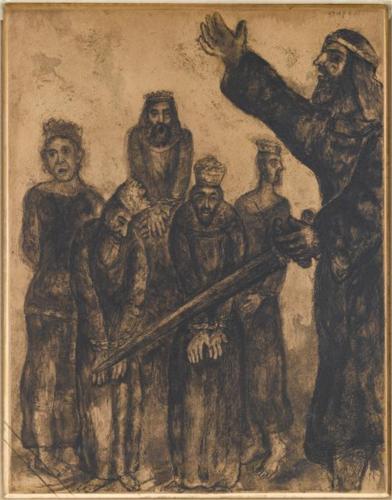

Joshua Delivering the Five Kings of Canaan to Israel’s hands and Preparing Them To Death, Marc Chagall, 1956

It is easy to see the philosophical traps the first horn of Euthyphro’s Dilemma falls into. It is a tempting position, an apparent easy out for Christians attempting to reconcile evil with their faith. Yet, in the end it only implicates God as an arbitrary, subjective force that could just as well be evil as it could be good.

Let’s contrast God as the sole arbiter of morality, as well as all of these other moral justifications presented by apologists, with what we really know about morality. Morality from an empirical, scientific point of view. Although we do not have a complete science of morality (we cannot measure units of evil, for example) this is not necessary for many moral questions. All we need is a basic framework that shows some degree of shared morality. And we have that. Theists, read: this is how objective morality without God works. This is how we know the genocide of Canaan is evil, be it history or literary fiction.

Research has shown morality has, if not specific objective rules, an objective framework or set of objective foundations (Haidt & Joseph, 2004). Research has also indicated morality has a correct developmental path, just as we would expect for other aspects of cognition (Kohlberg & Hersh, 1977). We are able to deal with moral deviants; we diagnose Antisocial Personality Disorder (4th ed., text rev.; DSM–IV–TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) and recognize psychopathy (Hare, 1995). We have discovered that morality is a result of brain functions – it is natural to all humans and damage areas of the prefrontal cortex impairs our ability to make moral judgments (Moll & Oliveira-Souza, 2007). We have a much better explanation for the source of universal moral values, their development in health human beings, their development in moral deviants and the biological basis behind both. A much, much better explanation than “God said so.”

Justifying genocide flies in the face of everything we know about healthy moral development. It raises questions – are these people psychologically deficient (a la Haidt) or do they have some form of brain disease (a la Moll)? Have they simply been stunted in their moral development, essentially moral infants (a la Kohlberg)? Could it be worse? Perhaps justifications of genocide in a religious context indicate something more sinister, a genuine mental disorder. These may be extreme conclusions, yet when people go out of their way to excuse and justify genocide – despite all moral indications that genocide is evil – it does leave one wondering just what exactly is going on inside the heads of these people.

Citations

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Haidt, J., & Joseph, C. (2004) On Human Nature. Daedalus, 133(4), 55-66.

Kohlberg, L., & Hersh, R.H. (1977) Moral development: a review of the theory. Theory Into Practice, 16, (3), 53-59.

Moll, J., & Oliveira-Souza, R. de (2007) Moral judgments, emotions and the utilitarian brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 319-321.

The Hare psychopathy checklist: Screening version (PCL: SV) SD Hart, DN Cox, RD Hare – 1995 – Multi-Health Systems, Incorporated